Answering the call

Paramedic-turned-nurse Nathan Koranda is responding to mental health and addiction needs in his local community and abroad

May 3, 2023

Tom Ziemer

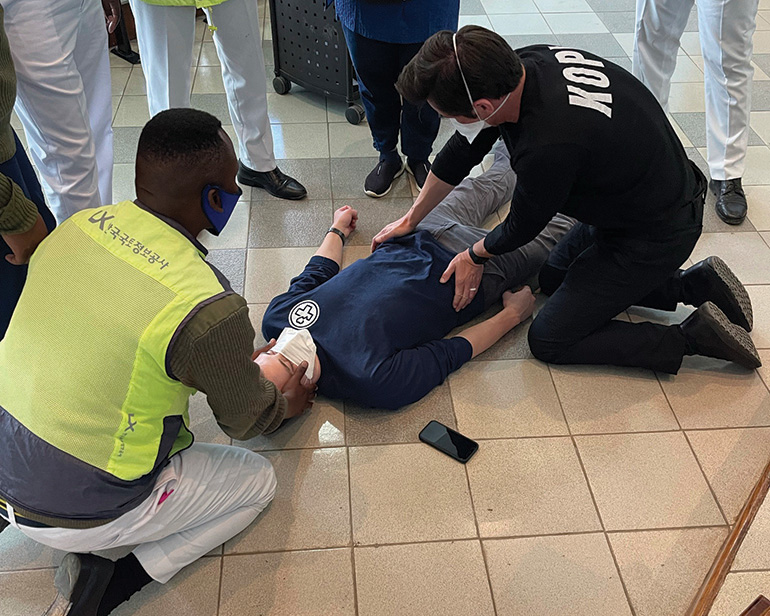

Above: From a paramedic to an RN, Nathan Koranda says nursing opened up many opportunities for him. He's now a DNP student in the psychiatric/mental health nurse practitioner specialty.

Standing in an ambulance bay outside Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis, Nathan Koranda tried to process a death that tore open his deepest of wounds.

Koranda didn’t know the victim, at least personally. But about a year earlier, Koranda had been one of the paramedics who had reversed that same individual’s overdose. And the man’s profile and circumstances had reminded Koranda of his own brother’s death from a heroin overdose, a tragedy that pushed Koranda to become a paramedic in the hopes of reversing a single overdose. He wound up handling nearly 100 over six years in the field.

The heartbreaking outcome not only conjured up painful personal memories; it forced him to consider how his profession was stuck in the midst of a seemingly unending opioid epidemic.

“We’re saving lives, but there’s not really that much on the other end of things to keep people locked into sobriety and keep them alive,” says Koranda, who identifies as being in long-term recovery from addiction for the past 15 years.

In nursing, he saw a different role—one he’s occupied for the past five years as a psychiatric nurse at PrairieCare in Brooklyn Park, Minnesota. And he’s currently taking the next step in his nursing career as a student in the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) program in the psychiatric/mental health nurse practitioner specialty.

“You’re working with people for a longer period of time, and you’re caring for them in a different capacity. That's something I wanted to be a part of,” says Koranda, BS, RN, PHN, who will graduate in May. “As far as advanced practice nursing goes, I honestly believe that’s the future of health care. Granted, I’m biased, but I think that as a profession we’re going to continue to grow in some pretty remarkable ways, and I want to be a part of that.”

Koranda has already made his own remarkable contributions to the world, even before entering the DNP program. In 2018, he and a fellow paramedic traveled to Arusha, Tanzania, to lead six weeks of education and training around emergency medical services for local doctors and nurses. Arusha, like many other cities in the east African country, lacks a formal emergency medical services system, with those responsibilities generally falling to police officers.

“If you look globally, trauma in general takes more lives than HIV, malaria and tuberculosis combined, but receives only 1% of the world’s global funding for care,” says Koranda.

That first trip to Tanzania turned into the nonprofit KOPI, which Koranda launched in 2019 to bring together emergency medical services education and mental health training. KOPI teams have returned to Arusha three more times to train police officers, partnering with a local psychologist to incorporate mental health components. KOPI already has plans to expand its work into another region in Tanzania in 2024.

“All of the concepts are developed locally by the stakeholders out there. We’re just the instrument that’s used to carry some of that out,” says Koranda, who is KOPI’s executive director. “I believe that they would be successful without KOPI. We just happen to be lucky enough to be participants in that work.”

Closer to home, KOPI has partnered with a host of local entities to create the Minneapolis Addiction Recovery Initiative (MARI) Safe Station project. Funded by a federal grant through the Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant, and Substance Use Program, the project allows individuals experiencing substance use disorder to visit designated fire stations, where they’re evaluated, paired with a peer recovery coach in a matter of minutes, and connected to a host of resources and services.

“It’s a new entry point into the system that’s hopefully breaking down a barrier to care,” says Koranda, who learned about a similar program in Rhode Island while presenting on a panel in Washington, D.C., in 2017.

KOPI is filling a void—something Koranda also hopes to do through his work as an advanced practice nurse in the psychiatric, mental health and addiction treatment space. According to a 2020 survey by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, less than half of U.S. adults with a mental illness received treatment. More than 155 million people in the U.S. live in areas with a shortage of mental health professionals, per statistics from the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Koranda sees himself among a wave of nurses who are willing to respond to that need.

“Nursing has opened up a lot of opportunity for me,” he says. “It really allows a lot of flexibility for me to chase after all of this stuff that I care about that I have never had that opportunity before. I feel very lucky and blessed to be a part of the profession. I think about it often. Yeah, sure it’s a lot of work, but it’s a lot of really good work, and I wouldn’t want to be doing anything else right now.”